An Introduction to Session Types

Let’s start out with a dramatis personæ.

Dramatis Personæ

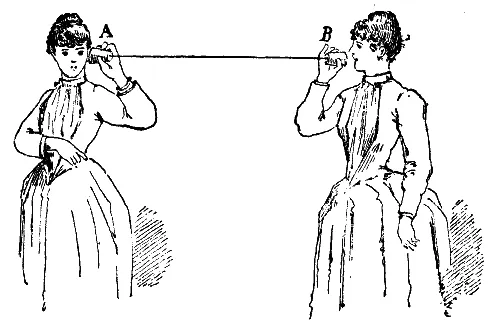

Session types are about channels, which are like tin can telephones, in that you can use your tin to whisper sweet little nothings to every friend who has a tin connected to yours. I know, my love for tin can telephones is betraying my age a little—I’m an old Victorian lady.

“You simply must try my milk puddings, Ada”, Briar whispers into the telephone.

“You simply must try my milk puddings, Ada”, Briar whispers into the telephone.- Ada

- A Victorian Lady.

- Briar

- Ada’s Lady Friend.

- The Tin Labelled A

- A Tin Held by Ada.

- The Tin Labelled B

- A Tin Held by Briar.

- The Piece of Twine

- A Piece of Twine Connecting Tin A and B.

In the vernacular of session types, the tin cans are referred to as channel endpoints or simply endpoints, and the collection of all tin cans held together by the twine is referred to as a channel. A series of messages whispered back and forth over a single channel is referred to as a session.

Most of the literature on session types considers only the classic scenario, in which we connect exactly two tin cans to form a channel—this is referred to as binary session types. Yet if we wanted to, we could make a telephone with any number of tin cans—this is referred to as multiparty session types.

In this blog post, we I’ll focus on binary session types

Session Types at a Glance

Let’s imagine for a moment that Ada were to take Briar up on her offer, and ask her to sample her famous milk puddings. Briar, a proper lady, only offers her milk puddings to those who make a sufficiently polite request—Ada must be polite and say “please”, but she must not overuse it, lest she comes off as begging!

We encode the interaction between Ada and Briar using session types in Haskell:

- Ada’s requests are represented using the

Requestdatatype, which allows us to prefix a request for pudding with any number of uses ofPlease. - Briar’s response is represented using the

Responsedatatype, in which she can either grant permission, in which case Briar sends anAllowwith a sample of pudding attached, or refuse Ada’s request, in which case she sends aDenywith a reason.

The functions ada and briar represent Ada and Briar—these functions each receive an endpoint for the shared channel, and communicate along the lines of our story—Ada sends a request, Briar evaluates her politeness and responds with either pudding or a refusal, and finally Ada evaluates Briars response, and expresses her emotions accordingly:

data Request

= Please Request

| MayIHaveSomePudding

data Response

= Allow Pudding

| Deny String

ada :: Send Request (Recv Response End) -> IO ()

ada chan = do

chan' <- send (Please MayIHaveSomePudding) chan

(resp, chan'') <- recv chan'

case resp of

Allow pudding -> putStrLn "I’m so happy!"

Deny reason -> putStrLn "Woe is me!"

briar :: Recv Request (Send Response End) -> IO ()

briar chan = do

(req, chan') <- recv chan

let resp = case req of

MayIHaveSomePudding -> Deny "Such rudeness!"

Please MayIHaveSomePudding -> Allow myPudding

Please (Please _) -> Deny "Such beggary!"

chan'' <- send resp chan'

The example illustrates a crucial notions for session types:

Firstly, session types are communication protocols. If you glance at the types of the endpoints, you see that they represent the communication protocol from each participants perspective. For instance, Ada’s endpoint says she must send a request, receive a response, and then end the session.

Secondly, the types of the endpoints of a binary channel must be dual. When Ada’s endpoint says she must send, Briar’s endpoint says she must receive. For classical multiparty session types, the equivalent notion is called coherence, but the principle remains the same.

Finally, each endpoint must be used exactly once if we want to be sure to stick to the protocol. For instance, in the code above, each channel endpoint is only used once, and each send or receive returns a new channel on which to continue the communication. If we didn’t, we would be able to write a cheeky variant of Ada, who simply tries any number of pleases until she gets that sweet, sweet pudding:

ada :: Send Request (Recv Response End) -> IO ()

ada chan = tryAll MayIHaveSomePudding chan

where

tryAll req chan = do

chan' <- send req chan

(resp, chan'') <- recv chan'

case resp of

Allow pudding -> putStrLn "I’m so happy!"

Deny reason -> tryAll (Please req) chan

But that’s not what the protocol says! Briar doesn’t have time for more than one request, so after the first one has run its course, Ada whispers her second request into the tin can, then waits forever, pining for a response from Briar which will never come!

A Bit of a Roadmap

Only a few short years after Ada and Briar enjoyed sweet milk puddings, a man by the name of Alonzo Church was born in Washington, D.C., in the United States. Three decades later, in the 1930s, Alonzo developed the λ-calculus, a foundational calculus which studies computation using functions. To this day, the λ-calculus underpins most theories of functional programming languages. Talk about influential!

Only a few short years after Alonzo developed the λ-calculus, a man by the name of Robin Milner was born near Yealmpton, in England. Alonzo lived a long life, over nine decades! A few years before Alonzo’s death in the mid 1990s, Robin, together with Joachim Parrow and David Walker, developed the π-calculus, a foundational calculus which studies concurrent computation by processes using message-passing communication. It wasn’t the first process calculus—it itself was heavily influenced by ideas dating back to the early 1980s—but it’s certainly one of the most influential!

We’ll start out by discussing the untyped λ-calculus. It’s a wonderful little language, and it’s really powerful. Unfortunately, it has all sorts of programs that do all sorts of bad things, like loop forever, so with all that power, it’s really scary too! We’ll then discuss the idea of taming all that scary power using types, to try and get only well-behaved programs, and the challenges of taming it without taking all the oomph out.

Then, we’ll switch to discussing the π-calculus. It’s a wonderful little language, even if it’s twice as big as the λ-calculus—with six constructs instead of three! It’s even more powerful than the λ-calculus—it can express all sorts of concurrent behaviours that the λ-calculus has no hope of expressing. Unfortunately, it’s scarier as well—there’s way more things that can go wrong! Again, we’ll turn our attention to taming all that scary power using types, and the problems of oomph’lessness that comes with it.

Finally, we’ll talk about having the best of both worlds, in a concurrent λ-calculus, which is sorta what you get when you smash the λ-calculus and the π-calculus together at high speeds! The concurrent λ-calculus has the best of both worlds: higher-order functions and concurrency with message-passing communication!

The λ-calculus! (So powerful, so scary…)

The untyped λ-calculus celebrated its 89th birthday last November, so to say that it’s been around for a while undersells it a bit. It’s a pretty small system—it has only three things—there’s variables, λ-abstractions to make functions, and function applications to get rid of ‘em:

There’s only one computation rule—if a function

That’s not all, though, since we also need to let our calculus know that it’s okay to reduce under a function application. For this, we could just write out the following rules:

However, things tends to compose a little better if you use a little trick called evaluation contexts. We’ll see an example of how evaluation contexts compose better later. Anyway, you write down all the partial terms under which it’s okay to normalise, and then write a single rule… Read

When we choose what to put in our evaluation contexts, we determined where to allow and disallow reduction. For instance, here we’re saying “You’re allowed to reduce function calls and their arguments… but don’t you dare touch the function body before we’re actually calling it!” This is called an evaluation strategy, and the one we’re using here is called call-by-name. Usually, call-by-name is pretty terrible in terms of efficiency. Imagine you have a pretty expensive computation, and the result of that computation is used twenty times… call-by-name is likely to do the whole computation twenty times! In practice, you’ll want to use call-by-value or call-by-need, but those complicate things, so we’re not using them here!

Where were we? Oh, yes, λ-calculus, powerful, scary… Right! The λ-calculus is very powerful—some stuff about it being a “universal model of computation”—but that power comes at the cost of also being able to express quite a lot of scary programs that do bad stuff.

For instance, the λ-calculus comes with general recursion out of the box, via the

That’s good—as programmers, we like recursion! Really simplifies your programs, not having to write out the case for every possible input!

However, if you pass

That’s scary, I’d prefer not to have that! Programs which run forever, but never do a single thing—or worse, programs which are doing things the whole time, but never produce any outputs!

Most functional languages don’t just implement the core λ-calculus, but rather extend the λ-calculus with various constructs—numbers, addition, multiplication, pairs, sums, etc. Technically speaking, these can all be encoded using just functions—see, e.g., Church encodings—but it tends to be a lot more practical and faster to use, e.g., machine numbers.

For example, we can extend the untyped λ-calculus with Peano numbers. First, we extend the term language with the number zero, written

Then, we extend the reduction rules with two reduction rules for pattern matches on numbers—depending on whether the number is zero or a successor:

And we shouldn’t forget to extend our evaluation contexts:

We can now define addition on Peano numbers in our calculus! Ideally, we’d write something like the following, familiar definition for addition:

Our core language doesn’t support recursive or pattern matching definitions, so we’ll have to elaborate the above definition into something less familiar, which uses the

Woe is us! We have another kind of problem! We now have to worry about programs like

Problems like these are less obvious when using, e.g., Church encodings, since everything is just functions. For instance, if we use Church-encoded Peano numbers to compute

All in all, we’ve identified two main problems with using the untyped λ-calculus as a foundation for programming languages:

- it has programs which loop forever but produce nothing; and

- it has no way of making sure that data is used as intended.

Specifically, for the second problem, we have the choice between programs which get stuck and programs which compute nonsense. If we want programs that misuse data to get stuck, we tag our data—by using, e.g., a syntactically distinct

Taming the λ-calculus with types…

So, we’ve got a lot of scary stuff going on, stuff we really rather wouldn’t have, like programs which uselessly loop forever, and programs which try to add numbers to functions. What can we do?

One of the simplest solutions—horrible pun absolutely intended—is to use simple types. You see, in 1940, in an attempt to get rid of these unhelpful loops, Alonzo developed the simply-typed λ-calculus.

We start by formalising what we mean by type. Since all we’ve got is functions, all we need is a function type

With types in hand, we write down some typing rules. The goal is that if we can construct a typing derivation for a term, that term will be well-behaved.

Terms are checked in the context of some typing environment, which we’ll refer to with the variable

We write

Inference rules are like a puzzle. They’re written as…

The puzzle you’re trying to solve is:

- Find a piece whose conclusion matches the thing you’re trying to prove;

- Oh no! All those things had premises! You gotta find puzzle pieces whose conclusions match those as well now!

- Keep going until there’s no more open premises! You got this!

For the simply-typed λ-calculus, there are three inference rules, one for each term construct:

Oh no! All of these rules have some premises! Does that mean we’re gonna have to puzzle forever? Nope, all it means is that we are immediately complicating the puzzle analogy.

If you look at the first rule, the premise isn’t actually a typing judgement… It’s one of those thingies which checks whether or not

All those puzzle pieces say is “if you wanna know if

Anyway, back to our typing rules for the λ-calculus! In order of appearance:

- A variable

has type if there’s an assignment in that says so. - If we’ve got something of type

which uses something of type from the typing environment, we can abstract over that something to create a function of type . - If we’ve got something of type

and something of type , then we can apply the former to the latter to get something of type .

Guess what?! It works! All the programs you can type with these rules are super well-behaved and nice! Buuuut… there’s kinda a lot of programs that are really nice and good, that you can’t type with these rules… Very, very, notably, you can’t type the

Queue the history of type theory, trying to wrangle with this, trying to make this system more permissive while still keeping lots of the scary stuff out!

It’s, uh, pretty hard to get extactly the bad looping stuff out, so some folks are like “eh, we’ll keep the looping stuff, but still use types to get rid of all that ‘adding functions to numbers’ nonsense”, whereas other folks are all hardcore and decide that “no it has to be terminating all the way even if it becomes pretty hard to use!”

A detour into linearity!

Let’s briefly talk about another type system for the λ-calculus—but only because it’ll turn out to be highly relevant to session types, I haven’t forgotten what I promised to write about! Let’s talk about the linear λ-calculus.

In its most minimal form, the linear λ-calculus demands that every variable is used exactly once. This’ll end up being a very important restriction for our session-typed calculus. Remember that cheeky implementation for Ada, which kept sending new and new requests for milk pudding, even though the protocol clearly stated she could only send one request? That’s where the used exactly once restriction comes in.

Okay, so how are we going to enforce this in the type system? When you check a function application, you have to decide which parts of the typing environment are gonna be used in the function, and which parts in the argument. By the time you’ve made it all the way down to a variable, the typing environment is supposed to be empty save for the variable you’re checking. Everything else must’ve already been split off for usage elsewhere.

Also, we now use this cute little lollipop instead of the function arrow:

In order of appearance:

- A variable

has type if the typing environment only contains . - If we’ve got something of type

which uses something of type from the typing environment, we can abstract over that something to create a function of type . (It’s the same as before!) - If we’ve got something of type

which uses some chunk of the typing environment called , and something of type which uses the rest of the typing environment called , then we can apply the former to the latter to get something of type which uses both and .

Notice that

As a type system, this is highly restrictive. Essentially, what we’re left with is a calculus of permutations. Think of lists… if you’re writing a function from lists to lists, but you have to use every element in the list exactly once, what kinds of programs can you write? Permutations. That’s it.

The π-calculus! (Is even scarier…)

Oof, that was a bit of a detour, wasn’t it? Wanna talk about session types, the thing that I promised I’d talk about? Okay, let’s do it! The π-calculus is pretty young—it didn’t show up until 1992, though it’s heavily influenced by ideas dating back to the 1980s. Unlike with the λ-calculus, there’s not really a canonical π-calculus that everyone agrees on, so the one I’m presenting here is just kinda the version that I felt like presenting.

It’s also pretty big! It’s got twice as many things in it as the λ-calculus. Instead of functions, we’re talking about processes, which are built using six different constructors:

In order of appearance:

- We’ve got ν-binders, written

, which creates a new channel , which can be used in . (That ν is the Greek letter nu, which sure sounds a lot like “new”. It’s, like, the only well-chosen Greek letter we use in programming language theory.) - We’ve got parallel composition, written

, to let you know that two processes are running in parallel. - We’ve got nil, written

, the process which is done. - We’ve got send, written

, which sends some on , and then continues as . - We’ve got receive, written

, which receives some value on , names it , and then continues as . - We’ve got replication, written

, which represents a process which is replicated an arbitrary number of times.

Replication isn’t truly essential to the π-calculus, it’s just that we can’t do any sort of infinite behaviour with just sending and receiving, so we have to add it explicitly. Other solutions, like adding recursive definitions, work as well.

There’s only one computation rule—if we’ve got a send and a receive in parallel, we perform the communication, and replace all instances of the name bound by the receive instruction by the actual value sent:

Plus our usual trick to let us reduce under parallel compositions and ν-binders:

However, these rules in and of themselves are not enough. You see, a parallel composition

Why not? The send and the receive are in the wrong order—our computation rule requires that the send is to the left of the receive, so we can’t apply it:

One solution is to tell the reduction semantics that the order of processes doesn’t matter—along with a few other things:

In order of appearance:

- Parallel composition is commutative and associative, i.e. the order of parallel processes doesn’t matter.

- We can remove (and add) processes which are done.

- We can remove (and add) ν-binders which aren’t used.

- The order of ν-binders doesn’t matter.

- We can swap ν-binders and parallel compositions as long as we don’t accidentally move an endpoint out of the scope of its binder.

- Replicated processes can be, well, replicated. We kinda forgot to add this at first, so we didn’t have any infinite behaviour… but now we do!

Now that we have this equivalence of processes—usually called structural congruence—we can embed it in the reduction relation:

The reason we’re embedding it this way, with a reduction step sandwiched between two equivalence, is because the equivalence relation isn’t super well-behaved—there’s plenty of infinite chains of rewrite rules, e.g., imagine swapping

If you thought the λ-calculus had problems, have I got news for you. There’s all the old problems we had with the lambda calculus. We’ve got processes that reduce forever without doing anything:

Ah! One process which just keeps sending the value

Plus, if we add numbers, we could try to send over the number 5, foolishly assuming it’s a channel.

But what fun! There’s new problems as well! If we’ve got two pairs of processes, both of which are trying to communicate over

Another fun thing we can do is write two processes which echo a message on

To be fair, it’s not surprising that race conditions and deadlocks show up in a foundational calculus for concurrency—it’d be weird if they didn’t. But that does mean that as programming languages people, we now have two new problems to worry about! To summarise, we’ve identifier four main problems with the untyped π-calculus as a foundation for programming languages:

- it has programs which loop forever but produce nothing;

- it has no way of making sure that data is used as intended;

- it has race conditions; and

- it has deadlocks.

Taming the π-calculus with types…

Oh dear, so many problems to solve. Where do we begin?

It may help to think a little deeper about the latter three problems. In a sense, we could see a deadlock as the consequence of us not using a channel as intended. After all, we probably intended for one party to be sending while the other was receiving. We could see a race condition in a similar light. We intended for the two pairs of processes to communicate in a predictable pattern, in pairs of two.

These are overly simplistic descriptions—sometimes we truly don’t care about the order of messages, and a bit of a race is fine. However, much like with the λ-calculus, we’re gonna try and cut all the bad stuff out first, no matter what cost, and then get to the business recovering what we lost.

Let’s have a look at session types, invented in the early 1990s by Kohei Honda, and let’s focus first and foremost on one important property—session fidelity. Essentially, it means that we communicate over a channel as intended by its protocol—or session type.

Let’s start with the simplest system, where there’s only two things we can do with a channel—send and receive. That’ll be our language of session types—either we send on a channel, we receive from a channel, or we’re done:

A crucial notion in session types—as mentioned in the introduction—is duality, the idea that while I’m sending a message, you should be expecting to receive one, and vice versa. Duality is a function on session types. We write duality using an overline, so the dual of

Finally, before we get to the typing rules, we’re gonna make one tiny tweak to the syntax for processes. Before, our ν-binders introduced a channel name, which any process could then use to communicate on. Now, ν-binders introduce a channel by its two channel endpoint names. It’s gonna make the typing rules a bunch easier to write down:

We’ve also gotta propagate this changes through the structural congruence and the reduction rules. It’s pretty straightforward for most of the changes—just replace

Okay, typing rules! One thing that’s very different from the λ-calculus is that the typing rules only check whether processes use channels correctly—the processes themselves don’t have types. There are six rules, corresponding to the six process constructs:

In order of appearance:

- If we’ve got a process

- If we’ve got two processes

- The terminated process is done—it doesn’t use any channels.

- If we’ve got a channel

- If we’ve got a channel

- Finally, if we’ve got a channel which is done, we can forget about it.

This type system is linear, much like the linear λ-calculus we saw earlier. Told you it’d be relevant! Anyway, it’s not linear in quite the same way, since channels can be used multiple times. However, each step in the protocol has to be executed exactly once!

So, did it work? Are we safe from the bad programs? Yes and no. Which, uh, kinda just means no? But there’s some bad programs we got rid of! There are no longer programs which misuse data, since everything strictly follows protocols. Since every channel has exactly two processes communicating over it, we no longer have any race conditions. Furthermore, because those two processes must act dually on the channel, we no longer have any deadlocks within a single session—that is to say, as long as each two processes only share one means of communication, we don’t have any deadlocks. Unfortunately, it’s quite easy to write a program which interleaves two sessions and deadlocks:

We also don’t have looping programs anymore, but, uh, that’s mostly because we removed replication, so… win?

How do we get rid of those last few deadlocks? The ones caused by having multiple open lines of communication with another process? There’s several different ways to do this, and they all have their advantages and disadvantages:

The first option, used in, e.g., the logic-inspired session type systems by Luís Caires and Frank Pfenning and Philip Wadler, is to just say “The problem happens when you’ve got multiple open lines of communication with another process? Well, have you considered just not doing that?” Essentially, these type systems require that the communication graph is acyclic—what that means is that, if you drew all the participants, and then drew lines between each two participants who share a channel, you wouldn’t draw any cycles. This works! Can’t share multiple channels if you don’t share multiple channels, am I right? But it’s a wee bit restrictive… Got some homework about forks and hungry, hungry philosophers you need to do? Nope. Wanna write a neat cyclic scheduler? Not for you. However, it has some nice aspects too—it composes! Got two deadlock-free programs? Well, you can put ’em together, and it’s gonna be a deadlock-free program! If we updated our typing rules, they’d look a little like this:

We’ve glued the ν-binder and the parallel composition together in a single operation which makes sure that one endpoint goes one way and the other the other.

The second option, developed by Naoki Kobayashi, is to just do a whole-program check for deadlocks. Take out a piece of paper, and draw a blob for every dual pair of send and receive actions in your program. For every action, if it has to happen before another action, draw an arrow between their blobs. Finally, check to see if there’s any directed cycles—for each blob, see if you can follow the arrows and end up back at the same blob. We can do this formally by adding some little blobs to our session types—since each session type connective corresponds to an action—and requiring a particular order on the little blobs. For reference, little blobs are more commonly known as priorities. If we updated our typing rules, they’d look a little like this… first, we add little blobs to our session types. Duality preserves priorities:

We also define a function,

Then we change the typing rules:

We’re enforcing two things here:

- If we write

- If we connect two endpoints,

There’s a really nice recent example of a session type system which uses this technique by Ornela Dardha and Simon Gay. The upside of this technique is that you can have all sorts of neat cyclic communication graphs, and still rest assured knowing that they don’t do anything scary. The downside is that it’s a whole-program check, meaning that if you’ve got two deadlock-free programs, and you put ’em together, you have to check again, to see that you didn’t introduce any deadlocks.

Anyway, we’ve now got a mostly safe foundation for session types! You don’t see type systems this simple touted in papers much—or at all, as far as I’m aware. The reason is probably that they’re kinda too simple. Just like with the purely linear λ-calculus, there’s not much you can actually compute with these programs, and you have to put in a little bit of work before you can actually get to a point where you get back enough expressivity to be taken seriously as a programming language. However, I thought it would be illustrative to discuss the simplest possible type systems.

Once we’ve got this foundation, we can get to work extending it! With a little bit of effort we could add branching, replication, recursion, several forms of shared state, polymorphism, higher-order processes, etc. However, figuring out how all this stuff works in the context of the π-calculus seems like a bit of a waste, especially when we already know how they work within the context of the λ-calculus. Plus, doesn’t that “adding higher-order processes” thing sound suspiciously like adding higher-order functions?

Concurrent λ-calculus (λ and π, together forever)

Okay, this will be the final computational model I’m introducing in this by now rather long blog post, I promise! The point of concurrent λ-calculus, in short, is this: the π-calculus is great for modelling concurrency, but it’s a rather, uh, unpleasant language to actually write programs in, and instead of figuring out how to make it a nice language, why not just smash it together with a thing that we already know and love!

So, here’s the plan: we’re gonna start with the λ-calculus as a model of sequential computation, and then we’re gonna add a smattering of π-calculus processes on top as a model of sequential computations running concurrently.

First off, we’re going to take our λ-calculus terms, and extend then with some constants

Second, we’re going to wrap those terms up in π-calculus processes—we’ll have ν-binders and parallel compositions, and threads which run terms. There’s two kinds of threads—main threads, written

So what are the semantics of our calculus going to be?

First off, we just keep the reduction rules for our λ-calculus—and we’re just gonna sneak those rules for units and pairs on in there while you’re distracted. We’re gonna call this reduction arrow

Let’s not forget our usual “evaluation context” shenanigans:

We’re also going to just copy over the structural congruence from the π-calculus, best as we can—the, uh, terminated process has disappeared, and in it’s place we’ve now got child threads which are done, i.e.,

Then we copy over our rules from the π-calculus… but what’s this! We don’t have send and receive in the process language anymore? They’re all awkwardly wedged into the term language now… So terms reduce, and at some point, they get stuck on a

…which sure looks a lot like our π-calculus rule. Unfortunately, it only captures top-level

This is a great example of why evaluation contexts compose better! Try and write this rule without them! Oh, yeah, almost forgot! We’ve still gotta add evaluation contexts for the process language, plus that thing where we tell reduction that it’s okay to rewrite using our structural congruence, and a new rule where we tell π-calculus reduction that it’s okay for them to use the λ-calculus rules as well:

We’re almost done! You might’ve noticed that we’ve got

Oof, we’ve done it! We’ve got the whole reduction system!

Two Victorian Ladies (More Formal, Somehow?)

Our formal concurrent λ-calculus is getting pretty close to being able to encode the interaction between Ada and Briar! Remember that, like a billion words ago? There’s two problems left, if we want to encode our example:

- Ada prints a string, but we don’t really have strings or, uh, the ability to print strings.

- Ada and Briar send values of data types back and forth, but we don’t have data types.

For the first one, we’re just gonna take

For the second one, well, we can make this work without having to add full-fledged data types to our language. See, the request data type… it essentially encodes the number of pleases, right? It’s kinda like Peano numbers, where MayIHaveSomePudding is Please is the successor Response? Well, Ada doesn’t actually use the pudding or the reason, so that’s pretty much just a Boolean… and those should be relatively easy to add! First, we extend our terms:

Then, we extend the reduction rules with two reduction rules for if-statements—one for when it’s true, and one for when it’s false:

And we extend our evaluation contexts:

Great! Now we can encode our example!

And let’s put it all together in a single

Right, let’s see if our encoding does what we think it should do! I’m gonna spare no detail, so, uh, very long series of evaluation steps coming up.

Whew, so far so good! The

Yes, we’ve shown that our program is correct! It makes Ada happy! What more could you want?

Taming the concurrent λ-calculus with types…

Types? Is it types? It should be! Just because our happy example works out, doesn’t mean the calculus as a whole is well-behaved. See, we can still encode cheeky Ada, who’ll do anything for that sweet, sweet pudding:

I’m not gonna write out the whole evaluation, like I did with the previous example, but you can verify for yourself that evaluation gets stuck after a single back-and-forth, with Briar being done with Ada’s cheek and reducing to

We’d like to rule out this sort of failing interaction a priori. Briar was very clear about her boundaries of only taking a single request for cake, so we should’ve never set her up with cheeky Ada. How are we gonna do this? With types!

Developing the type system for the concurrent λ-calculus will be a very similar experience to developing its reduction semantics… we’re mostly just smashing stuff from the λ-calculus and the π-calculus together, and seeing what falls out.

To start off with, we’re gonna copy over the whole type system for the linear λ-calculus, adding the rules for units and pairs as needed. Similar to how we write

First come the rules for variables and functions, which we’ve seen before:

- A variable

- If we’ve got something of type

- If we’ve got something of type

Then, the rules for units:

- We can always construct the unit value, and doing so uses no resources.

- If we’ve got something of the unit type

And finally, the rules for pairs:

- If we’ve got something of type

- If we’ve got something of type

Great, that settles it for our term language, doesn’t it? Oh, right! We’re gonna have to give types to

Remember duality on session types? Yeah, we’re also gonna need that:

Okay, and we’re finally ready to give types to our concurrency primitives:

In order of appearance:

Right, so that’s terms properly taken care of. What about processes? To the surprise of, I hope, absolutely nobody, we’re pretty much gonna copy over the typing rules from the π-calculus, best we can. There’s one small difference. Remember how we were marking threads as either main or child threads, and only the main thread could return a value? That’s gonna show in our typing rules. First off, we’ll have two ways of embedding terms as processes—either as a main thread or as a child thread—which will show up in the typing judgement:

The premises here refer back to our term typing rules, but the conclusions uses our process typing rules. In our process typing judgements, we’re marking which kind of thread we’re dealing with on top of the

We’re not listing what

Phew, I think that’s it! We’ve got typing rules! Specifically, we’ve now got typing rules which ensure that the session protocol is followed… so we should be able to show that the interaction between Ada and Briar is well-typed. I’ll leave it up to you to verify this, as the proof is quite big and I’m pretty tired of typesetting things by now. And, great news, cheeky Ada is not well-typed! There’s two reasons—one is a bit cheeky, but the other one is a bit more satisfactory:

- We cannot type cheeky Ada because we have no recursion (cheeky).

- We cannot type cheeky Ada because she uses the communication channel repeatedly, which violates linearity (satisfactory).

Unfortunately, this type system for the concurrent λ-calculus has similar problems to the type system we showed for the π-calculus… it’s really very restrictive, and yet it still has deadlocks if you start mixing multiple sessions. Fortunately, the same solutions we gave for the π-calculus can be used here. Philip Wadler has an example of the first solution, where you glue together ν-binders and parallel composition, in a calculus he calls Good Variation. Luca Padovani and Luca Novara have an example of the second solution, where you do a global check to see if you have any cyclic dependencies.

Session End

Whew, that sure was quite a number of words! Let’s look back on what we learned:

The λ-calculus

- The untyped λ-calculus is a really neat model of computation, but it’s got some problems, namely programs which do nothing forever, and programs which do silly things like adding numbers to functions.

- There’s several approaches to mitigate these problems via type systems, but it’s always a struggle between how many bad programs you rule out versus how many good programs you rule out with them—and how unwieldy your type system gets.

The π-calculus

- The untyped π-calculus is, like the λ-calculus, a really neat model of computation, and it’s even more expressive, in that it can model concurrency. However, this comes with all the problems of concurrency. Suddenly, we find ourselves facing deadlocks and race conditions!

- There’s several approaches to mitigate these problems via type systems, but again, it’s always a struggle between how many bad programs you rule out versus how many good programs you rule out with them—and how unwieldy your type system gets.

The concurrent λ-calculus

- We can smash together the λ-calculus and the π-calculus to get the concurrent λ-calculus, with the best of both worlds—it has higher-order functions and can model concurrency—and the worst of both worlds—now you’ve got to reason about higher-order functions and concurrency!

- Unsurprisingly, the semantics and type systems for the concurrent λ-calculus look a lot like what you’d get if you smashed the semantics and type systems for the λ-calculus and the π-calculus together, but there’s some tiny tweaks we need to make to get them to behave like we want to.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading altogether too many words! If you didn’t—how are you reading this?!—thanks for reading whatever number of words you thought was appropriate.

Disclaimer: I haven’t proven any safety properties for any of the calculi presented here. The simply-typed λ-calculus is pretty well established, so you can trust that’s good, but the other systems are potentially destructive simplifications of existent systems, so all bets are off! I guess you could do the proofs yourself—or if you wanna be really safe, refer to the papers I’ve linked. However, I’ve opted to make these simplifications because the smallest typed π-calculi which are actually expressive tend to be pretty big already